Mask Work of Art Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History the Metropolitan Museum of Art

View of archaeological and ethnographic collections (Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford) (photo: Jorge Royan, CC: By-SA 3.0)

When early European explorers brought dorsum souvenirs from their trips to the African continent they were regarded as curiosities and they didn't find a abode in art museums for centuries. Instead, these objects became office of natural history museums—along with fossilized remains, flora and beast, and purely commonsensical objects. They were considered the man-made material remains of a civilization. Overcast by the framework of Social Darwinism in the 19th century and other beliefs that justified racial hierarchies, peoples of African, Pacific, and Native American descent were regarded every bit less civilized, even less human being. Attitudes nigh their art were also determined past pre-conceived ideas about race and therefore, their creations were not categorized as "Art" in Euro-American sense.

Plank Mask (Nwantantay), 19th-20th century, Bwa peoples, forest, paint, fiber, 182.9 x 28.2 x 26 cm, Burkina Faso (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

By the early 1900s all the same, these aforementioned objects that were initially regarded as artifacts of textile culture, began to exist exhibited in Western fine art museums and galleries as "fine art." The objects themselves had not changed, but there was a shift in the attitudes and assumptions well-nigh what constituted a piece of work of fine art.

To historicize this issue more, nosotros tin divide the history of the brandish and reception of African art into four periods. In the eighteenth century, objects like the ones illustrated hither would likely exist housed in a "curiosity chiffonier"—in a private family parlor where trinkets and novelties acquired over generations, often while traveling, were displayed. The artist, civilization, and role of these objects was not commonly recorded or regarded every bit significant. Past the nineteenth century, many of these marvel cabinet collections were donated first to natural history museums where they were categorized and classified in the name of scientific discipline along with flora, animate being, and skeletal remains. By the twentieth century, some of these same works were exhibited in fine fine art galleries and museums. Over time, African art has become widely collected and ever more than popular.

Some of the assumptions about what constitutes art is still very much a function of the Western aesthetic arrangement. For instance, "loftier art" is still thought of as painting and sculpture. Because many African artworks served a specific function, Westerners accept sometimes not regarded these as art. It is worth remembering, however, that the concept of "art" divorced from ritual and political office, is a relatively recent evolution in the West. Prior to the 18th century, well-nigh artistic traditions around the world were functional besides as artful, and arguments can be fabricated that all art serves social and economic functions. The objects that African artists create—while useful—embody aesthetic preferences and may be admired for their form, composition and invention.

Eighteenth-century theories

In Eighteenth-century Europe, philosophers and critics constructed a definition of "art" in which the object was unique, circuitous, irreplaceable, inspired by the natural world, and with the exception of architecture, non-functional. In contrast, non-Western art was viewed equally not unique, simply produced, replaceable, abstract, and utilitarian. Therefore, Non-Western art was not considered to exist art.

Nineteenth-century theories

Nineteenth century notions of art were redefined by theories of cultural development. Social Darwinism was used to back up the claim that all cultures progress along an evolutionary ladder. Western culture was seen as the virtually avant-garde and inherently superior. Societies in Africa were viewed as more than primitive, a state of beingness from which mod Western society evolved. Franz Boas in 1927 in his volume Archaic Fine art shows that cultural evolutionism is seriously flawed. He argued that gimmicky societies cannot exist arranged on a ladder of "least evolved" or "most advanced." Nor can their art.

Twentieth-century-cultural relativism and Pablo Picasso

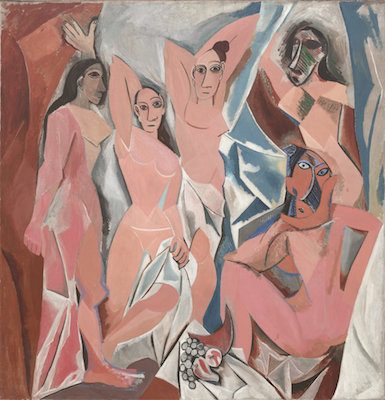

Pablo Picasso, Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, 1907, oil on canvas, 243.ix ten 233.7 cm (The Museum of Modern Art)

Anthropologists and art historians came to realize that non-Western cultures should not be judged co-ordinate to the values of the Westward, leading to a reevaluation of the nature of "art." Nonetheless, it was modern Western artists who brought non-Western objects into the popular imagination as works of fine art worthy of aesthetic consideration. Looking for a new way to represent modernity, artists such as Andre Derain, Amedeo Modigliani, and Pablo Picasso turned to non-Western fine art for stylistic inspiration. Nosotros meet this in Picasso'due southLes Demoiselles d'Avignon (above). The women's faces on the right of the canvas take been painted as masks inspired by African artworks Picasso observed on his trip to the Trocadero Museum in Paris in 1907:

All lone in that atrocious museum with masks, dolls fabricated by the redskins, dusty manikins. Les Demoiselles d'Avignon must have come up to me that very day, but not at all because of the forms; because it was my first exorcism painting — yes absolutely!…The masks weren't simply like any other pieces of sculpture. Not at all. They were magic things. But why weren't the Egyptian pieces or the Chaldean? We hadn't realized it. 'Those were primitive, not magic things. The Negro pieces were mediators. They were against everything — against unknown, threatening spirits. I always looked at fetishes. I understood; I too am against everything. I understood what the Negroes used their sculpture for. Why sculpt similar that and not another fashion? After all, they weren't Cubists! Since Cubism didn't exist.

In the quote to a higher place, Picasso recognized that the African and Amerindian artists whose work he saw at the museum in Paris were deliberately using abstraction. He doesn't focus on why they chose this manner just he adopts it, none-the-less, to pursue his own expressive interests. For contemporary avant-garde artists, African art offered abstraction as a strategy for the representation of modernity. The quote too tells us that Picasso, like many Western collectors, didn't know much nigh the function, culture, or history of African objects and he seems to have focused on their purely formal properties. Picasso, Piet Mondrian, Constantin Brancusi, Georges Braque and other modernists helped Western viewers to see these objects as "art" but the cultural meanings of these works remained opaque. Still, over the course of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, scholars began to question social Darwinism and seek out indigenous interpretations of the class and function of objects.

Today, many gimmicky African artists are influenced by tradition-based African art (see for example, El Anatsui). African arts played a central office in their communities, whether to communicate royalty, sacrality, inner virtues, aesthetic interests, genealogy, or other concerns. Equally the art historian Robert Farris Thompson has argued for the Yoruba, African fine art is used to make things happen, it is efficacious and necessary for events like rituals, masquerades, and life cycle transitions to successfully occur.

Additional resource:

African influences in Modern Art on The Metropolitan Museum of Art's Heilbrunn Timeline of Fine art History

Collecting for the Kunstkammer on The Metropolitan Museum of Art'south Heilbrunn Timeline of Fine art History

Source: https://smarthistory.org/the-reception-of-african-art-in-the-west-2/

0 Response to "Mask Work of Art Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History the Metropolitan Museum of Art"

Post a Comment